Post-Luxury Status Symbol #3: Aspirational Parenthood

In 2026, the baby is the new Birkin.

In the world of the wealthy, where far more people than the Maisons would prefer can buy their handbags - or better yet, get a knock-off at Walmart - raising children emerges as the one thing that simply cannot be duped.

From Survival Strategy to Status Symbol

The idea of a ‘big family’ being low status is a holdover from a time that no longer exists: a time when you had twelve kids, three died, and five went to work on your farm.

For most of human history, motherhood and fatherhood weren’t deliberate life projects. They were consequences - of heterosexual marriage, limited contraception, religious norms. A cultural script running on autopilot. Large families signalled lack, a survival strategy. You didn’t time the market on your fertility or calculate your career capital to absorb the shock of a newborn. You just had them.

Now it’s the exact opposite. Having a big family has become, in some ways, the ultimate status symbol, because it requires several forms of privilege operating simultaneously.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The rising cost of living means you need significant financial stability just to live comfortably with children. You need active support systems through family or paid childcare. You need enough accumulated career capital to take parental leave without it being career suicide.

The Unbothered Parent

On a deeper layer, it’s not just about having children - it’s about maintaining your pre-parenthood lifestyle whilst having them. Still seeing friends. Still showing up at clubs or events. Not being exhausted all the time. Not wearing clothes with a bit of baby puke on them.

Given the heightened expectations around wealth codes and their subtleties, the market has already responded with alternatives to maintain that lifestyle - for a price, obviously. Baby water pilates. Raves with kid-safe headphones. Seventeen-course omakase fine dining with your five-year-old.

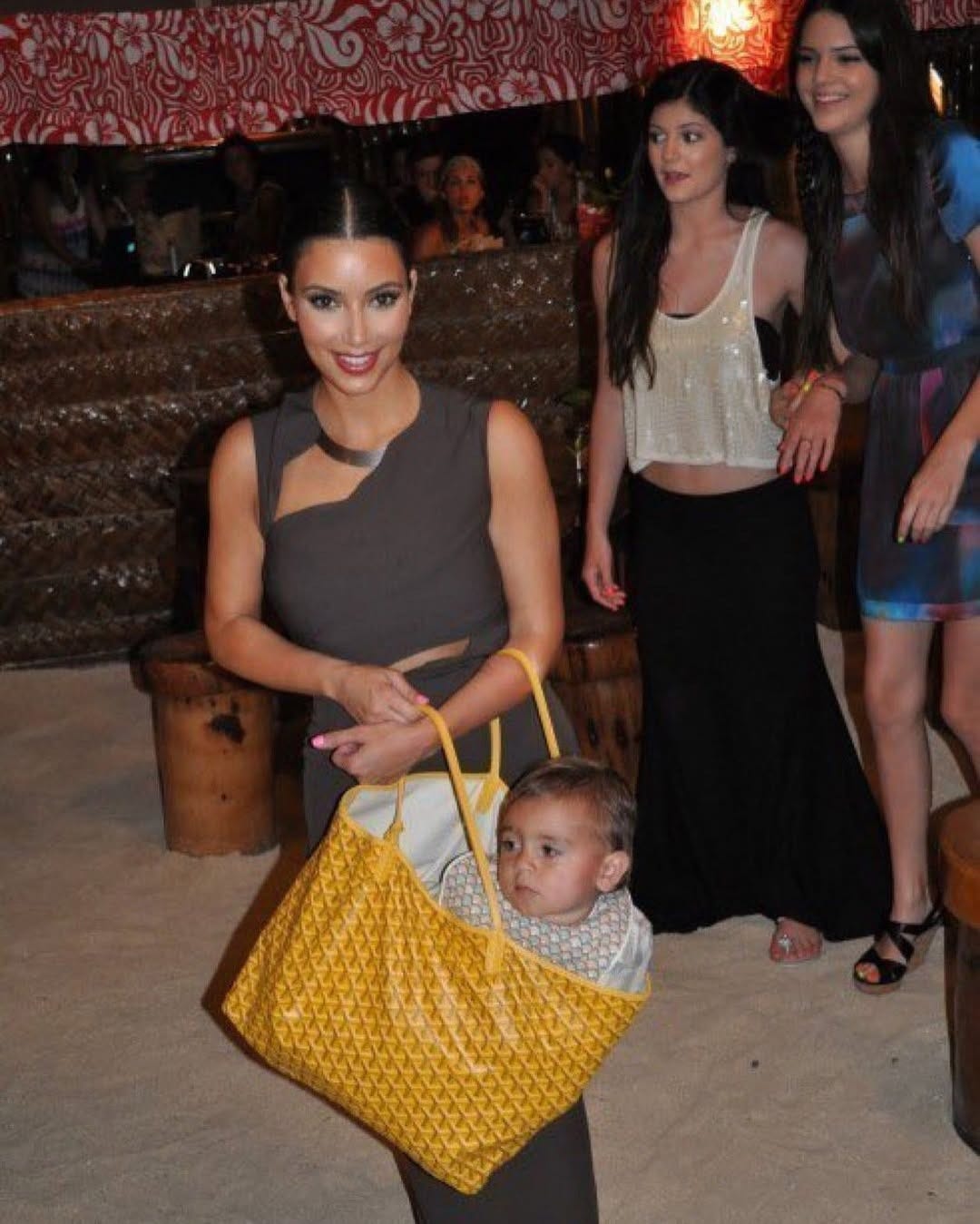

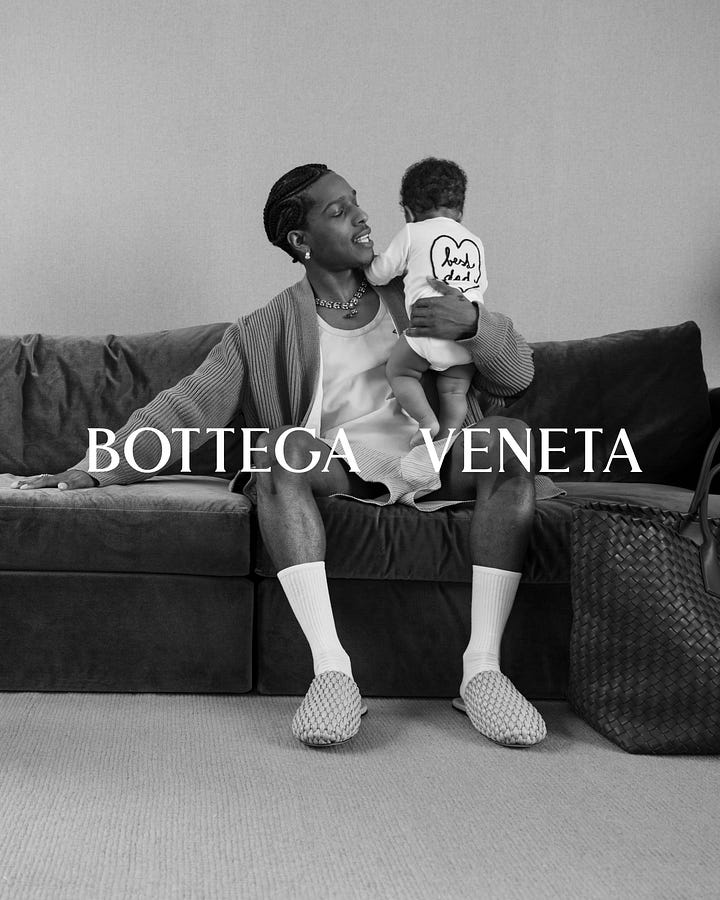

The performance completes itself when parents insist their children’s style must harmonise with their own. For every type of parent, there’s now a corresponding brand for their children. Whilst legacy kids’ brands like Toys “R” Us decline, luxury fashion houses launch exclusive childrenswear collections.

Think of Bottega Veneta’s Portraits of Fatherhood campaign with A$AP Rocky. Or brands like Coterie - a luxury nappy subscription service - and Artipoppe, whose baby carriers cost upwards of $700. In contrast to traditional baby brands that centre the child in their imagery and emotional core, these brands treat children almost as luxury accessories to the parents’ life.

Both effectively enshrine parenthood as cultural performance - not just a life stage, but an intentional choice signalling a maturing of taste and preferences.

Optimism as Flex

Having children also signals something darker: confidence in the future despite the world around us being, to put it kindly, not the best. It’s no longer science fiction to imagine environmental collapse by 2040, yet we remain fixated on overpopulation in developing nations - because we’ve been told that’s always the problem, never overconsumption.

Malcolm Harris has argued that millennials’ reluctance to have children isn’t selfishness - it’s rational economic calculation in a system designed to extract rather than support. Which makes those who do have multiple children either extraordinarily privileged or extraordinarily optimistic. Often both.

And if we look closely at who seems most secure about the future, it’s no coincidence that many are part of the actual top one per cent. Phenomena like tradwives, who romanticise the past to justify beliefs about who should be reproducing, or billionaire families opting for large broods, raise a question: for whom is this future being built?

When Age Becomes Aspirational, Child Rearing Becomes Content

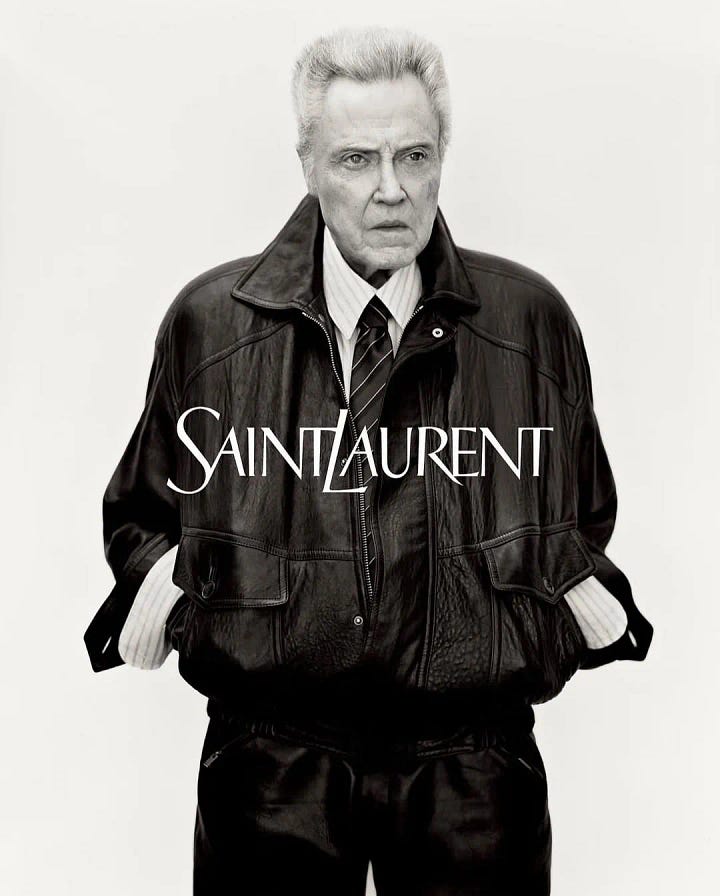

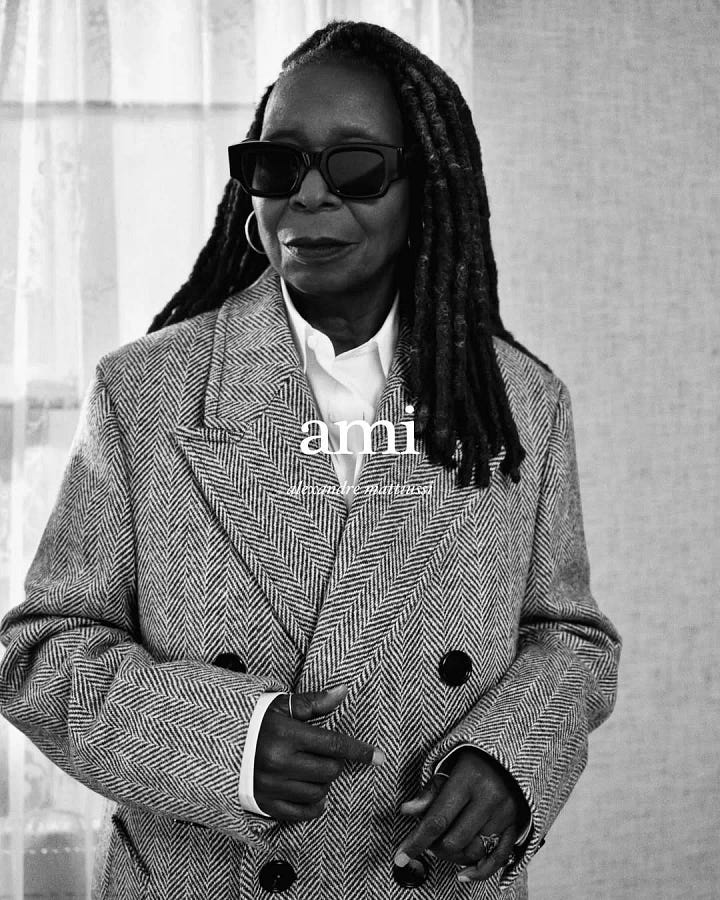

What’s remarkable here isn’t just that parenthood has become aspirational. It’s that it’s replaced eternal youth as our culture’s central (or at least, sole) desire. For decades, the beauty and wellness industries were built on denying age, on maintaining the appearance of perpetual youth. Now we’re witnessing an inversion: maturity, visible parenthood, age diversity - these are becoming high status.

We’re cresting over the hill of peak image culture, and what lies on the other side is the permission to age, to reproduce, to exist in bodies that bear the marks of time and biology.

But for every silver lining there’s a cloud - one that reveals itself in the children themselves. Both dynamics sell the idea that you can remain sophisticated despite the chaos of parenthood.

But parenthood was never meant to be sophisticated. It’s chaotic, loud, messy, disordered - and also full of light and colour. Arguably the hardest thing you’ll ever do. By flattening it into an aesthetic performance, we reduce childhood to something two-dimensional. Something that exists not for itself, but as extension of parental identity.

This raises uncomfortable questions. To what extent can you shrink a new life into an aesthetic designed only to mirror you? What does it mean for a child to grow up as part of their parents’ brand identity?

Shoshana Zuboff warned that surveillance capitalism doesn’t just extract data - it shapes behaviour from the moment it begins tracking. For children born into Instagram, curated from birth, there is no “before”. Their earliest memories are already performances. Their sense of self is formed under the assumption that they exist, at least partially, for an audience.

We learned to perform in front of social media. Millennials at least remember a life offline - we formed identities before we documented them. Gen Alpha has no such luxury. What happens to a child who learns, from day one, that in front of the camera they are not themselves, but whatever version the audience wants to see? How does personality form when your reality is fragmented through lenses you can’t yet comprehend? What happens when childhood itself becomes content - monetised, optimised, algorithmically distributed?

A childhood curated for Instagram is not a childhood at all. It’s just “cool”.

A reminder: if you’d like to continue the conversation on this article, head to the free subscriber chat for an accompanying reading list and discussion questions.

The discussion question for this week: For those of you who are parents or considering parenthood, how do you navigate the tension between the genuine chaos of raising children and the cultural pressure to maintain your pre-parenthood identity?

And for everyone: when you see parenthood performed online - the curated family photos, the designer childrenswear, the “unbothered parent” aesthetic - what does that make you feel about your own relationship to having (or not having) children?

Child-free and single here, my take is that this promotion of parenthood as a status symbol is yet another psy-op to encourage us to have children en-masse and feed capitalism. It’s interesting and insidious how these trends pick up when women around the world are actively refusing to have children in a world too expensive, corrupt and dangerous.

"How does personality form when your reality is fragmented through lenses you can’t yet comprehend? What happens when childhood itself becomes content - monetised, optimised, algorithmically distributed?" 💔